The Commander X16 (and some more BASICODE)

▼ The Commander X16 is an upcoming new Commodore 64 like 8-bit computer built from currently available parts, as explained in Youtube playlist. After watching some of the more recent videos, I decided to download the emulator... and tried out some BASICODE on it.

Why a new 8-bit computer?

Part of this is of course middle aged nerds wanting to relive their childhoods. Not discounting that aspect, I do think there was something special about the 8-bit home computers from the 1980s. Because those systems were so limited, they dispensed with all overhead and just gave you the minimum needed to write and run programs. So it was easy to write programs like games yourself.

And for some reason, for me at least, none of that translated to more modern systems like the Amiga. Not too long after I got an Amiga, I learned C in college, and ended up writing relatively low level code such as my own traceroute implementation. But I never wrote anything that uses the graphical capabilities of the Amiga, PC or Mac. (Unless you count some more recent web stuff.)

Now obviously those old computers can still be found, but it's getting harder and harder to use them, as compatible displays and I/O options are becoming more scarce. Some kind of emulation such as the THEC64 works well to run the old software more easily, but has nothing to do with the old hardware. Part of the charm of those 8-bit computers is that a single person can understand the whole thing, software and hardware.

Commander X16

So that's where the Commander X16 comes in. The basic idea is to start with a VIC-20, which is an extremely simple design with many parts still available, and then update some parts as necessary.

The biggest issue was finding a good graphics chip with abilities similar to the C64's VIC-II chip. They couldn't find any, so they use an FPGA-based video controller instead, with 128 MB of its own video RAM and also an SD card interface for storage. Audio options were also less than ideal, so it looks like they're also going to use the VERA FPGA video controller for audio.

The VERA will output 640x480 analog VGA, with various text and graphics modes.

The CPU will be an 8 MHz 6502. It's really too bad that they didn't choose the 65816, a backwards compatible 16-bit successor of the 6502. The X16 will have 40 kB of regular RAM (minus a bit for hardware registers) followed by 8 kB of "bankable" RAM. That's 512 kB or 2 MB of additional RAM, but the 6502 can't address that much memory, so at any one time, 8 kB of the extension RAM can be mapped into the 6502's address space. The ROM works in a similar way, with one 16 kB bank out of a total 512 kB available at any time.

The X16 will support a PS/2 keyboard and mouse as well as various extension options. Unfortunately, there is no RS232 port or any other way to communicate with the rest of the world included. So that means either an extension card or swapping out that SD card on a regular basis.

They eventually licensed the C64 BASIC and “KERNAL”, so BASIC programs or even machine code / assembly programs that only uses the system interfaces and don't try to directly use the C64 hardware will run on the X16. On the one hand, that's nice because it's familiar to people who've programmed on the C64 and it will be possible to port over C64 programs relatively easily, but on the other hand, even within the limitations of an 8-bit computer there are a lot of things we could do better these days. For instance, the C64 uses a weird variation of ASCII that makes exchanging text pretty annoying.

BASICODE on the X16

So I wanted to see what it would take to run BASICODE on the X16 using the emulator. I didn't know yet they'd licensed the C64 ROMs so I was surprised to see how compatible the X16 really is with C64 BASIC and C64 system calls. For the most part, the only thing I had to do is change my cursor position code a bit to use the official API call rather than jump directly to the KERNAL code.

But... Cursor positioning once again turned out to be my nemesis. Although the C64 has a 40-column screen, when you move beyond column 39, you continue on to 40, 41 and so on, until 79. That way, you can type lines of BASIC longer than 40 characters. So that creates trouble with BASICODE programs try to figure out the size of the screen. For the C64, I just made sure you couldn't go beyond column 39 and line 24.

The X16's default text mode is 80x60 and it can also run in 40x30. So I had to figure out which mode we're in to tell the difference between the actual column 40 on a 80x60 screen, or the face column 40 on a 40x30 screen. BASICODE programs may also try to figure out the size of the screen by specifying line 100 or so and see on which line they actually end up. But specifying a line outside the actual screen hangs the computer (or emulator). So I had to work around that, too. Eventually I managed to do all of that, and that same code now runs correctly on the C64 and the X16 both in 80x60 and 40x30 mode.

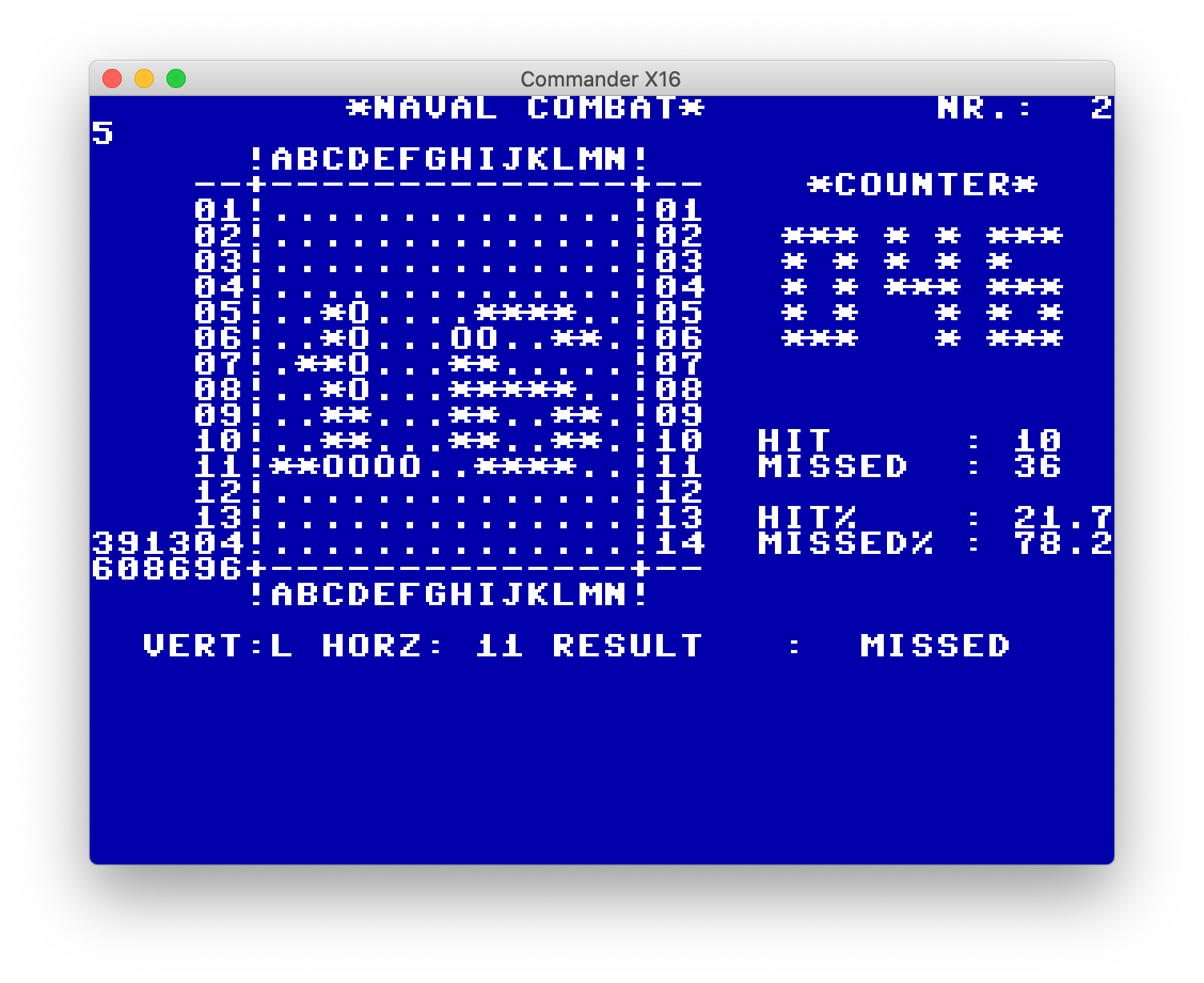

I've updated the my C64 BASICODE subroutines here. Here are some BASICODE programs in English. I like Sea Wars, which is a pretty good version of Battleship, which can run in Dutch, English, French and German. This is the PRG file that will run on the C64 or Commander X16: seawars.prg.

Permalink - posted 2021-05-30